Charlotte Bronte

PASSIONE E SCRITTURA.

«Finalmente arrivò il giorno (avevo diciotto anni) in cui aprii i miei occhi e scorsi il paradiso nella mia anima. Improvvisamente realizzai di avere una forza dentro di me...»

Adoro le tre sorelle Brontë (specialmente Anne) e le ammiro profondamente per le opere che sono riuscite a creare, per la profondità dei personaggi e l’analisi delle dinamiche relazionali di essi, nonostante le tre scrittrici abbiano in realtà avuto poca o nulla esperienza col “mondo esterno” e con l’alta società, che da piccole sognavano di frequentare. Figlie di un pastore irlandese e di una donna della classe media della Cornovaglia, furono costrette a trasferirsi nell’isolato Yorkshire, a Haworth, dopo la morte della madre. Anche la zia abbandonò la calda Cornovaglia per prendersi cura di loro. Haworth era un luogo poco salubre e l’aspettativa di vita degli abitanti della zona a quei tempi era molto bassa. Le sorelle maggiori, Maria ed Elizabeth, morirono da piccole a seguito della malnutrizione e delle condizioni di vita esecrabili subite alla Cowan Bridge School, una scuola femminile pensata prevalentemente per le figlie di uomini del clero della classe media. Anche Charlotte ed Emily la frequentarono e ne soffrirono, sia fisicamente che mentalmente e spiritualmente, finché il signor Brontë non decise di ritirarle dalla scuola. Soli nella brughiera, i piccoli Charlotte, Emily, Anne e Patrick Branwell crearono fantastici mondi con la loro immaginazione e da adulti direzionarono la loro vena creativa verso la letteratura e la poesia, sebbene solo le opere delle tre sorelle raggiunsero la popolarità.

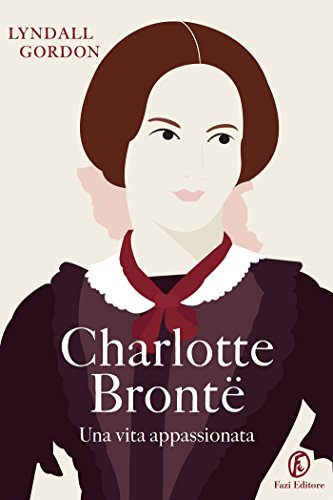

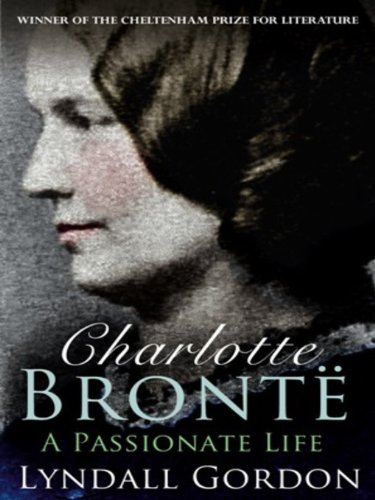

Nella biografia Charlotte Brontë, una vita appassionata, l’autrice Lyndall Gordon si focalizza appunto sulla passione che caratterizzò Charlotte per tutta la sua vita, sentimento che dovette però reprimere per via dei costumi dell’epoca vittoriana, che volevano le donne asservite, docili e ubbidienti. Secondo la Gordon, le eroine dei romanzi di Charlotte sono tutte rappresentazione di sé, della sua prigione interiore e del fuoco che la animava. La differenza è che nei romanzi le eroine hanno la possibilità (e decidono) di esprimersi per quello che sono e alla fine vengono ricompensate trovando un uomo che le capisce e le accetta così come sono. Sebbene questi parallelismi siano molto intriganti e in buona parte poggino su solide basi, a volte sono un po’ forzati, in quanto non ci sono sufficienti prove storiche a supporto di questa perpetua proiezione.

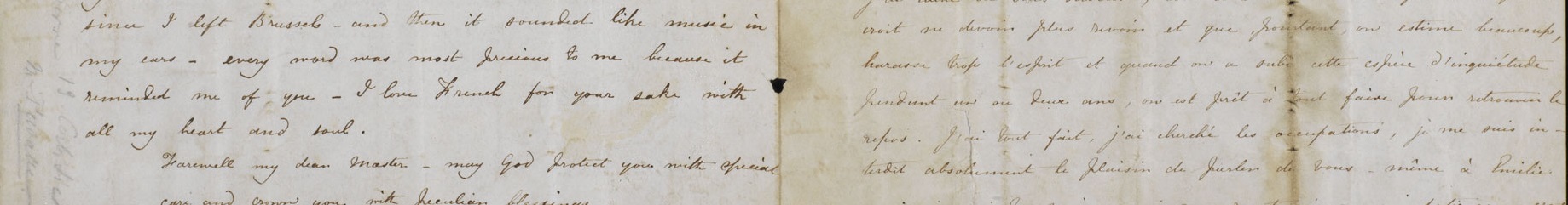

La Gordon ha fatto un ottimo lavoro di ricerca ed è precisa nei fatti storici riportati (estremamente interessanti sono le sezioni in cui vengono raccontate le esperienze che Charlotte e Anne hanno vissuto con l’insegnamento sia nel ruolo di studentesse sia in quello di governanti), ma sfortunatamente manca di trasmettere quella passione che è centrale nel libro. In altre parole, la Gordon parla di una donna appassionata in modo distaccato e freddo, il che rende la lettura a tratti noiosa e poco coinvolgente ed è solo grazie alla rilevanza dei fatti raccontati che si continua a leggere. Inoltre, come altre recensioni hanno fatto notare, alcune volte i parallelismi con la vita sentimentale di Charlotte (il professore del romanzo omonimo nonché il personaggio M. Paul Emanuel di Villette sono ispirati al professor Heger, di cui Charlotte si innamorò durante il suo soggiorno a Bruxelles, mentre l’uomo dapprima amato da Lucy in Villette è ispirato al suo editore George Smith) e l’analisi di alcuni brani dei romanzi e delle lettere sembrano inseriti nel libro come riempitivi, come se l’autrice non avesse altri fatti reali di cui scrivere e si fosse risolta a trovarli nei romanzi di Charlotte. Non c’è dubbio che i due uomini abbiano ispirato i personaggi di cui sopra, ma che ogni singola frase e comportamento di Jane e Lucy siano del tutto autobiografici, come se Charlotte non fosse in grado di creare personaggi autenticamente profondi con la sola immaginazione, è un po’ una forzatura.

Nonostante queste “debolezze”, la Gordon ha fatto un gran lavoro e ci ha regalato un’interessante biografia moderna di una grande scrittrice vittoriana. Oltre a quella della Gaskell, pubblicata nel 1857, edulcorata e non sempre veritiera, l’ultima biografia di Charlotte risale al 1967 ed è quella della “biografa delle Brontë”, Winifred Gerin, della quale scriverò in seguito.

Concludo con alcune delle citazioni che più mi hanno affascinata:

«Anche a scuola, a motivarla era il costante migliora di sé... Lo faceva per educare i suoi gusti. Diceva sempre che la necessità ci imponeva una dose già sufficiente di duro pragmatismo, e che la cosa più importante era smussare e raffinare le nostre menti. Serbava come se fosse oro ogni brandello di informazione relativa alla pittura, alla scultura, alla poesia, alla musica.»

«Il genio senza studio, senza arte, senza la conoscenza di ciò che è stato fatto, è forza senza freni, è l’anima che canta dentro e non può esprimere il canto interiore se non con voce ruvida a roca.»

«Affilate recensioni le avevano già insegnato che le persone sono spesso pronte a a diffamare una donna con una brutalità che generalmente non viene riservata agli uomini. A Dickens fu possibile limitare i pettegolezzi quando abbandonò la donna che era stata a lungo sua moglie per un'attrice diciannovenne, Ellen Ternan. False voci, al contrario, perseguitarono Charlotte non appena divenne famosa: qualcuno disse che a Londra non era andata a messa e aveva frequentato sale da ballo per tutta la settimana; qualcun altro che era stata respinta da uno, anzi tre curati, uno di seguito all’altro. Era consapevole della vendicatività cui si esponeva la “donna artista” che osava violare il modello di passività e silenzio imposto alle signore.»

PASSION AND WRITING.

“Finally a day came (I was eighteen) when I opened my eyes and glimpsed a heaven in my own soul. Suddenly I realized that I had a force within..."

I love the Brontë sisters (especially Anne) and I deeply admire the works and the profound characters they managed to create despite having little or no experience with "the external world" and the high society they aspired to mix with. Their father was an Irish clergyman and after their mother’s death they moved to Haworth, a village in Yorkshire, with their two other sisters, brother, father and aunt, who left the warmth of Cornwall to look after the children. At the time, Haworth was an unhealthy place and the life expectancy of the inhabitants was pretty low. The elder sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, died at a very young age following the abominable living conditions suffered at the Cowan Bridge School, a school mainly for the daughters of middle-class clergy. When Charlotte and Emily got sick too, Mr. Brontë removed them from the school. Alone in the moors, Charlotte, Emily, Anne, and their brother Patrick Branwell created amazing worlds with their imagination. As adults, they redirected their creativity to literature and poetry, although only the sisters gained success and popularity.

In Charlotte Brontë, A Passionate Life, author Lyndall Gordon focused on the passion driving Charlotte throughout her life, a passion she had to repress because it was an unacceptable quality for a Victorian woman, who was supposed to be submissive and obedient. According to Gordon, all Charlotte’s heroines represent her, her inner prison, and the fire burning within her. The difference is that her heroines can and choose to be themselves and eventually get rewarded by finding a man who understand and accept them as they are. These parallels are quite intriguing and are mostly based on a solid foundation, but at times they are a bit of a stretch, as there isn’t enough historical evidence to support this perpetual projection.

Gordon did an excellent research work and the facts are all there (I found particularly interesting the sections about Charlotte and Anne’s experiences with teaching, both as students and as governesses), but she’s unable to convey the passion which is the focus of the book. In other words, Gordon describes a passionate woman in a cold and detached way and this, to me, made the reading boring and underwhelming sometimes, so that I went on reading exclusively to learn the facts and events. Furthermore, as other reviewers noted, some parallels with Charlotte’s love life (the professor of the namesake novel and M. Paul Emmanuel of Villette were inspired by professor Heger, who Charlotte fell in love with during her time in Brussels, and the man first loved by Lucy in Villette was based on her publisher George Smith) and some of the analysis of the novels and letters seem to have been inserted in the book in order to fill for a lack of facts, as if the author had to find these facts in the novels. There’s no doubt that the two men mentioned above have played a great role in inspiring Charlotte, but it’s unlikely and a little far-fetched that each and every word or action by Jane and Lucy’s autobiographical, as if Charlotte wasn’t able to make up truly deep characters with her imagination.

Despite these “weaknesses”, Gordon did a good work and gave us an interesting, modern biography of a great Victorian author. Other than Gaskell’s, published in 1857, sweetened and not always accurate, the last biography of Charlotte is the one by Winifred Gerin, 1967, which I will write about in the future.

I want to end with the quotes that I most loved:

“Her idea of self-improvement ruled her even at school. She always said that there was enough of hard practicality... forced on us by necessity, and that the thing most needed was to soften and refine our minds. She picked up every scrap of information concerning painting, sculpture, poetry, music, etc., as if it were gold.”

“Genius without study, without art, without the knowledge of what has been done, is strength without the lever, it is the soul that sings within, and cannot express its interior song save in a rough and raucous voice.”

"Rude reviews had already taught her the willingness of people to slander a woman in a way from which men were exempt. Dickens was able to limit the talk when he dismissed his wife of many years for a nineteen-year-old actress, Ellen Ternan. False rumour, on the other hand, pursued Charlotte Brontë as soon as she became famous: one report was that in London she did not attend church but went to balls all week; another was that she had been jilted by one - no three - curates in succession. She was aware of vindictivness against the 'she-artist' who dared abandon the model of passivity and silence enjoined on women."